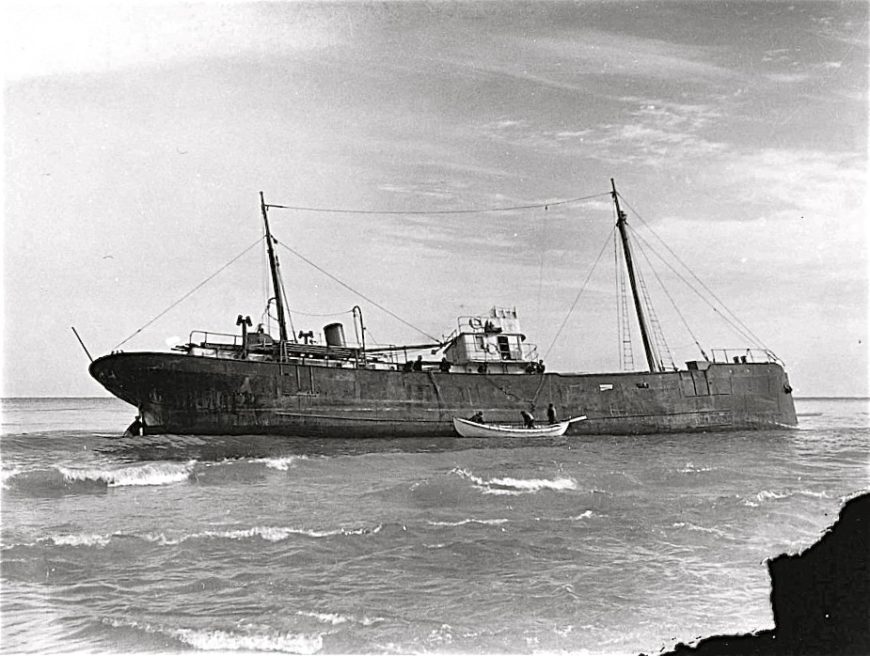

1939 Shipwreck Lutzen, Dubbed the Blueberry Boat

By Lou Ann Bowen

The 155-foot Canadian cargo ship Lutzen, aground off Cape Cod, 1939. This torn photograph and those below are in the collection of the Orleans Historical Society.

Early on the morning of February 3rd, 1939, Canadian Cargo ship Lutzen, on its way down the eastern seaboard to New York City, ran aground in shallow waters and heavy fog off Nauset Beach, near the Orleans, Chatham town line. As they were sailing around the Outer Cape, visibility was so bad that neither Captain Robert J. Randell nor any among his six-man crew were able to spot the Highland Light in Truro, nor the Nauset Light in Eastham. They had sailed right past them both.

Not long after, the bow of the 339-ton freighter screeched a terrible noise as it pushed into the soft sand a few hundred feet off the beach, between the Nauset Coast Guard Station in Orleans and the Old Harbor station in Chatham. The wreck had occurred within 100 yards of the spot where the Boston trawler Andover had grounded just five weeks earlier. On the Outer Cape, sandbars have been known to form a mile or more out from the beaches, making its shoreline one of the most treacherous on the east coast.

More than 1,000 shipwrecks have occurred along the 50-mile stretch between Provincetown and Chatham, leaving twisted skeletons now buried by shifting sands. But the Lutzen had such a gentle landing that there was no serious damage to the ship, although one crewman perished when he and a shipmate tried to launch a dory, which overturned in the heavy surf moments later.

All attempts to drag the Lutzen off of the sand and refloat it failed. After several days, salvage efforts were abandoned when the 339-ton ship tipped over on its side. –Collection of the Orleans Historical Society

All attempts to drag the Lutzen off of the sand and refloat it failed. After several days, salvage efforts were abandoned when the 339-ton ship tipped over on its side.

Over the next few of days there were a number of attempts to refloat the ship during high tides, but when a nor’easter came along and tossed the Lutzen farther up onto the beach, salvage efforts were abandoned, and attention was turned toward saving the unusual cargo. The 155-foot ship was loaded with frozen salmon, 100 barrels of cod liver oil, and 230 tons of frozen blueberries.

Some 50 Cape Cod men, each earning 75 cents an hour, were hired to offload the blueberries. The men worked diligently, and had unloaded nearly half of the fruit onto the beach in a single day, but a warm spell had set in, and it turned out that heavy freezer trucks couldn’t drive miles out onto the soft sand to load up and transport the blueberries to local industrial freezers, as supervising Coast Guard and customs officials had planned, so the berries were thawing fast.

Various accounts told of heavy seas that toppled the ship the next day, but shipwreck historian William Quinn gave a slightly different version of the demise of the “blueberry boat” in his 1973 book Shipwrecks Around Cape Cod. He maintained that the crews had indeed unloaded about half of the blueberries but had inexplicably removed them all from one side of the ship, and it simply tipped over on the next high tide. That ended all salvage efforts.

So people from all over the Cape began making their way to Nauset Beach to take home a big box of free blueberries. And that’s how the heavenly aroma of freshly baked blueberry pies ended up wafting from one end of Cape Cod to the other, in the dead of winter, 1939.

This mason jar of the blueberries from the 1939 shipwreck Lutzen, canned by Addie Williams of Skaket, resides in the collection of the Orleans Historical Society.

Lou Ann Bowen has been a year-round resident on Cape Cod since the 1980s. She has been a tour guide in Provincetown and in the dunes for more than 20 years and has written extensively about the area and it’s history for Provincetown Magazine and on her blog TheYearRounder’s Guide to Provincetown, found at ptownyearround.com. In 2015 she received the Best of Provincetown award for her writing as TheYearRounder.